When receiving this week’s assignment, I was asking myself the question what I understood by the word “race”. It is interesting that in English, it has more than one and quite diverse meanings – race as a local geographic or global human population distinguished as a more or less distinct group by genetically transmitted physical characteristics, race as a competition of speed, as in running or riding, race as a strong or swift current of water among others. I have to admit that I have faced this term very little. I remember to have needed to choose for the race within a form (usually, if I am not wrong, always in English) to determine my belonging. Where I come from, Latvia, there are practically only white people; this background creates at least two responses to the issue – one, people tend not to divide anyone in race distinctions, everyone is a human being, however on the other hand, lot of people are racist. Therefore, I understand “ethnicity” (cultural, ancestral classification) better than “race”.

Thinking about race issues in photography, I would like to mention David Goldblatt – white South African photographer who has worked a lot in Johannesburg – a mixed race city where blacks were suppressed; he did witness and immortalized the Apartheid where “black only” bus, for instance, was a reality.

- David Goldblatt

- David Goldblatt

- David Golblatt

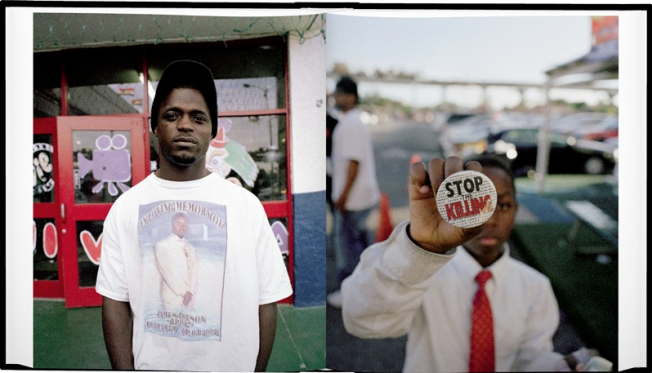

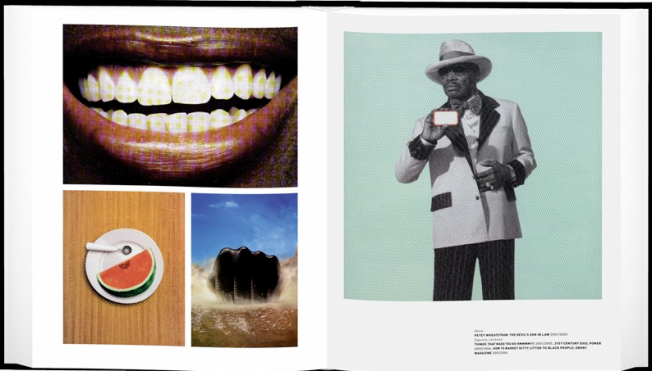

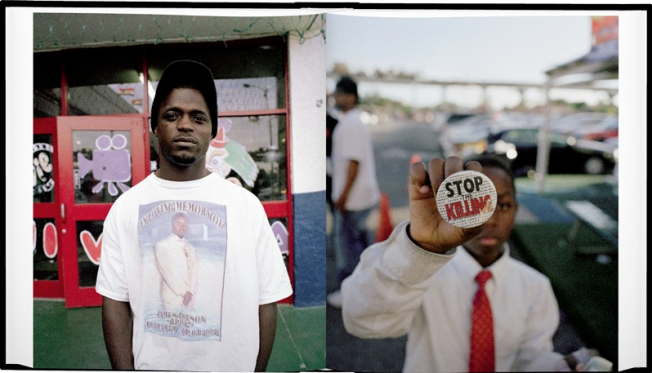

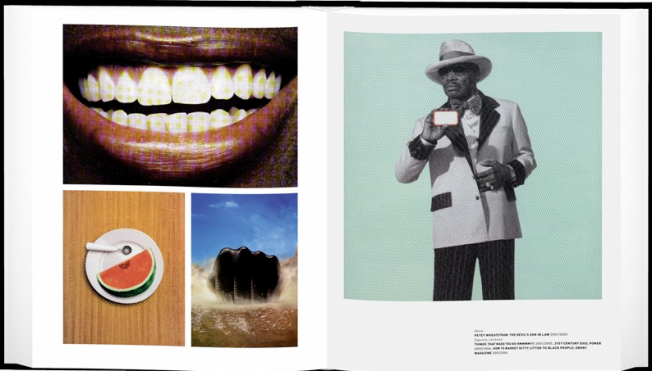

I also think of Hank Willis Thomas. His work that was published in book “Pitch Blackness” by Aperture in 2008 . The book begins with a deeply personal story of murder of young Songha Willis, the artist’s cousin, who was robbed at gunpoint and murdered outside a nightclub in Philadelphia in 2000. “It then charts Hank Willis Thomas’s career as he grapples with the issues of grief, black-on-black violence in America, and the ways in which corporate culture is complicit in the crises of black male identity.”

- Hank Willis Thomas

- Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas also has a very interesting body of work “Unbranded” (also published in the same book) where he examines the portrayal of African_american in advertising and media. He digitally removed all the text, so images could “speak for themselves”.

- Hank Willis Thomas

- Hank Willis Thomas

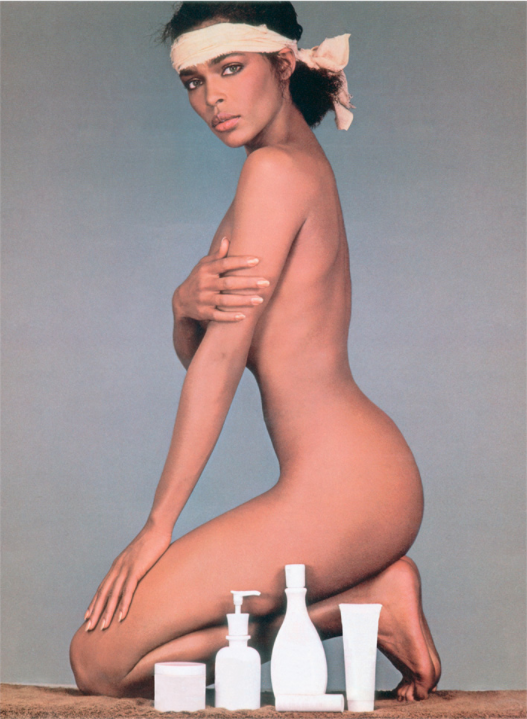

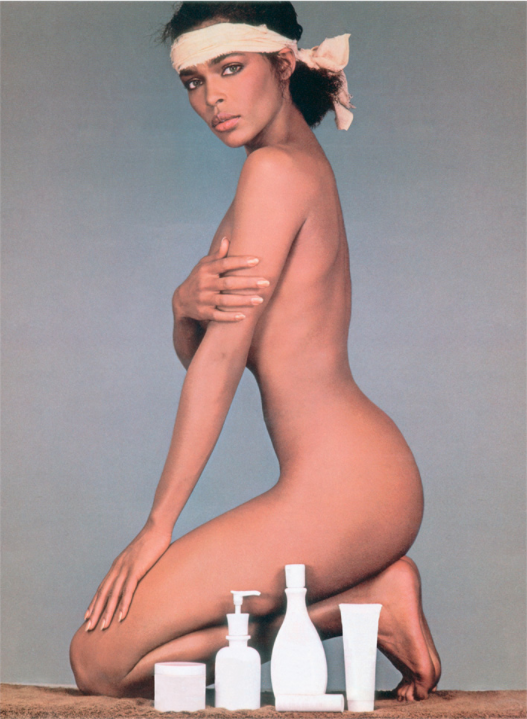

- Hank Willis Thomas, Caramel Cacao Butta’, Honey, 1982/2006

In this advertisement – commercial for body cream – a naked black woman is portrayed. It makes a reference to the color – Caramel Cacao butter makes us think it would be darker – therefore a darker woman is chosen to advertise it. In the meanwhile, the cream tubes are in white which makes me think that it is intended for white female audience. The model also have a fair headband – another reference to the duality. Her body posture is protective – to cover her breasts and her gaze looks more vulnerable than encouraging. The headband looks simple, quite outworn and makes me think of slavery – someone who has worked a lot and also needs a headband to absorb sweat.

Howard Winant – American sociologist and race theorist – starts off his text by a question what we really mean by the term, meaning that this term or its understanding today is more complicated than before. He argues that not to recognize race is a conservative approach; moreover, to try to replace “race” with another term, such as, “ethnicity”, “nationality” or “class” are mistaken initiatives. He is against both approaches – race as an ideological concept and as an objective condition. Winant first looks at the race as “an ideological construct”. He refers to the historian Barbara Fields who asserts that “the concept of race arose to meet an ideological need; its original effectiveness lay in its ability to reconcile freedom and slavery.” He summarizes Fields’ opinion as “extreme” – “ruled out by a theoretical approach.” Winant resumes that Fields’ opinion is incorrect for two reasons. First, “it fails to recognize the salience a social construct can develop [..] as a fundamental principle of social organization and identity formation.” Secondly, it fails to recognize that “race is a relatively impermeable part of our identities. U.S. society is so thoroughly radicalized that to be without racial identity is to be in danger os having no identity.” Reading this text is to learn more about American society for me because I cannot imagine hearing the latter statement about identity in Latvian society.

Then Winant looks at “race as an objective condition” – “sociopolitical circumstances change over historical time, racially defined groups adapt or fail to adapt to these changes, achieving mobility or remaining mired in poverty, and so on.” From there, race becomes a color-based category; Winant names it ridiculous and touches upon an interesting question – if somebody doesn’t act like black or white, is it a deviance from the norm? Here we can see the interaction of the subjects – Winant refers to performative aspect of race – the subject of last week’s readings. He summarizes why this approach fails too, firstly, “it cannot grasp the processual and relational character of racial identity and racial meaning”. Secondly, “it denies the historical and social comprehensiveness of the race concept.” And finally, “it cannot account for the way actors, individual and collective, have to manage incoherent and conflictual racial meanings and identities of everyday life.”

To offer a better, more comprehensive theory of race, Winant brings forward three conditions:

– it must apply to contemporary political relationships.

– it must apply in an increasingly global context.

– it must apply across historical time.

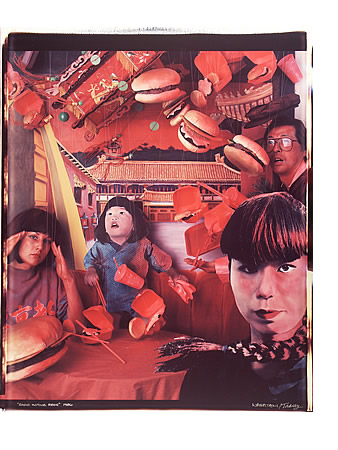

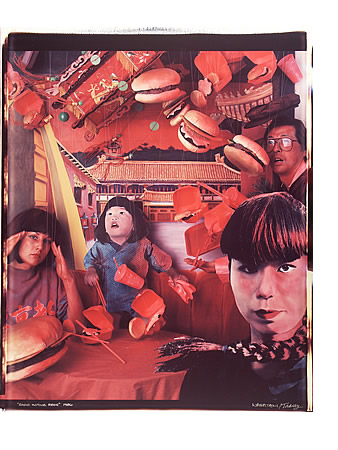

Winant is in position of creating a more substantial theory of race because he can read whatever was written before, evaluate it and “correct the mistakes”. It is to his advantage. In what concerns political aspect, Winant stresses that “binary logics of racial antagonism become more complex and decentered.” Winant offers a visual example from patrick Nagatani and Andree Tracey “Radioactive Redz”, 1986.

This polaroid has a dominant red color. There are four figures in it; the woman in the front has a direct look, woman at the left has put her hands at her temples as if having a headache. A girl at the background looks up with a surprised air and a man to the right has also surprised and lightly painful look. There is food falling from the ceiling – mostly hamburgers and other fast food items. At the background we can see a temple that makes me guess it refers to China. The red color too, might refer to the communism. But not all the people look Chinese. The woman on the left has a sweater on with Chinese hieroglyphs. The abundance of the food may rather refer to the U.S. However the title and the year make me think of Chernobyl catastrophe or nuclear age in more general terms.

On the global context, Winant adds that “racial space is becoming globalized and thus accessible to a new kind of comparative analysis.” He explains that today there are no (or less visible) borders between the countries (moistly between Europe and Norht America) which internationalizes and racialize “previously national polities, cultures and identities” and “various African pop styles leap from continent to continent.” He adds that “a global comparison of hegemonic social/political orders based on race becomes possible.” He stresses the importance of globalization (here we can go back to the subject of the first reading) in understanding the racial identity.

Finally, to his third point – the emergence of racial time – Winant comes up with a term “racial longue durée“, thus, associated with history, long term development.

I thought about National Geographic 125th issue’s story on “The Changing Face of America” – with photographs by Martin Schoeller National Geographic talks about the limitations of categories about race. Lise Funderburg writes: “The U.S. Census Bureau has collected detailed data on multiracial people only since 2000, when it first allowed respondents to check off more than one race, and 6.8 million people chose to do so. Ten years later that number jumped by 32 percent, making it one of the fastest growing categories.” “The Census Bureau is aware that its racial categories are flawed instruments, disavowing any intention “to define race biologically, anthropologically, or genetically.” And indeed, for most multiple-race Americans, including the people pictured here, identity is a highly nuanced concept, influenced by politics, religion, history, and geography, as well as by how the person believes the answer will be used. “I just say I’m brown,” McKenzi McPherson, 9, says.” And “A study of brain activity at the University of Colorado at Boulder showed that subjects register race in about one-tenth of a second, even before they discern gender.” If we accord so much attention to race, where is the line where it is an identification and where is the beginning of racial issues? Is the concern only how to define “What are you?” or the problem lies also in the fact that it is important to know? Howard Winant did say that it is rather ignorant to say that race doesn’t matter but among the answers the one “it doesn’t matter”, “I am a human as everyone is” or “multiracial” were often seen.

Photograph by Martin Schoeller

Michele Norris who has been collecting stories – 6 word sentences on the question “What are you?” later made a project “Race Card Project” where she asked to sum up the word “race”.

Holland Cotter – New York Times art critic – in his article “Photography Review; Cameras as Accomplices, Helping Race Divide America Against Itself”. He talks about race issues through an exhibition, occurred at International Center of Photograhy in 2003, curated by Brian Wallis and Coco Fusco – “Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self”. The exhibition, as says its annotation “looks at race as a distinct set of visual symbols that are manifested through a variety of photographic techniques. Taken together, “Only Skin Deep” is about how photography works to make us “see” race.” Cotter describes the show as “big, ambitious, confounding and confusing”. Interestingly, Cotter notes that the show “proposes that race, far from being a biological fact, is a value-laden social concept, a fiction. [..] “This concept permits a certain group of people to control other groups by establishing a system of hierarchical ranking and sustaining that ranking through physical and psychological force. Photography [..] has done much to create and perpetuate this whole fiction.” This last sentence is undoubtedly the most interesting for us. Cotter adds that “photography’s role – active and passive, overt and covert – in American racial politics has not yet been considered before on this scale.” (Here again, not only I can learn but also I have to admit that I don’t know American history or social and political life in details, therefore, it is not always easy to comment on different point of view, closely related to American context).

Holland Cotter mentions an image from Ken Light – “Strip Search in the “Shakedown Room” of the visiting area” (1994), from Texas Death Row. A young black male is undressing before the eyes of two white armed guards. Cotter states that a viewer cannot know if the man is a visitor or a prisoner, if this is a routine search or punitive, if he is a victim or a felon and concludes that the interpretation without straight facts is upon the viewer. Thus, we might be talking about power, racial stereotypes or abuse here. The two white guards seem to get weary of waiting or are just quite annoyed in general – the guard on the left is standing in an idle pose, a hand in his pocket, waiting. The black man stands with his back, probably hiding as much as he can from the guards. By his clothes – shorts and socks – it is really impossible to tell whether he is a prisoner or a visitor. If the latter, it would seem quite strange why one should fully undress for the inspection. There are no signs of physical abuse, the verbal or moral is more difficult to include in a photograph, however, to be undressed in from of two guards and also be photographed at the same time might be quite alarming experience.

Strip Search in the “Shakedown Room” of the visiting area (1994), from Texas Death Row. © Ken Light

Cotter mentions what other subjects within the topic are looked at the exhibition; those are assimilation, impersonation, but there are also witnessing, transcultures, “agains type” and origin story among others. Cotter concludes that this was a difficult but important exhibition to make.

Thelma Golden writes an introduction to the exhibition “Freestyle” (2001) at Studio Museum in Harlem. Golden introduces a term “post-black” which she had come up to with an artist friend Glenn Ligon. It refers to “black art” from the artists who didn’t want to be labeled as black artists. “Post-black was the new black.” The question on the topic – “what’s next?” after decades of activism – was raised beginning the new millennium. Golden found an answer within “freestyle”. The exhibition, as Golden says, “speaks to individual freedom that is a result of this transitional moment in the quest to define ongoing changes in the evolution of African-American art and ultimately to ongoing redefinition of balkiness in contemporary culture.”

Another article by Holland Cotter “ART/ARCHITECTURE; Beyond Multiculturalism, Freedom?”, published in 2001 in the New York Times introduces the article by saying that “multiculturalism will define the 1990’s in the history books as surely Pop defined the 1960’s.” He states that multiculturalism “exposed the social and ethical mechanisms of art and its institutions and called traditional aesthetic values into question. Most important, it reversed old patterns of exclusion and brought voices into the mainstream that had rarely, if ever, been there before.” It all led to the fact that the art world created specific ghettos, for instance, the above mentioned Studio Museum in Harlem which is ethically defined institution. Cotter notes an important thought: “Skin color is one of the defining facts of American life. If you don’t feel compelled to think about it much, chances are you are white.” A lot of problems related to racism were brought up by a new generation of teachers, writers, historians and museum personnel in the late 1980’s. He points out that ethnically selected exhibitions allowed those artists to exhibit more abut also brought a certain uniformity, favored certain ethnical myths, as well as making art about race was “stigmatized as “victim art”.” He continues by saying that race and class is not a problem for white (and middle class) but it is for minority artists.

Then Cotter mentions the 2000 census and the issue I talked about within National Geographic’s story on multi race categories. Here is Adrian Piper’s “Self-Portrait Exaggerating my Negroid Features”

And another portrait she did in 1995

The first one is a frontal, a serious portrait; she says she has exaggerated the features that makes her belong to black race – as she sees herself or as the society sees her, her belonging to a certain norm. A to the later portrait, Piper makes a portrait as being white but interestingly, not only she says she is white but specifically – Nice White Lady. Here she is being ironical – as white woman is a priori a nice lady and a black woman not.

Piper’s images also correspond to Cotter’s statement that “Artists can’t do all the changing. The art world has to change, too.” Cotter adds a thought that is so true and unfortunately, seems also very naive: “art is a “miracle”, a mysterious emanation of genius, a universal experience, transcending politics.” It should be like that that at least art doesn’t have to deal with the inequality, it shouldn’t be labeled.

Krista Thompson’s “The Sound of Light: Reflections on Art History in the Visual Culture of Hip-Hop” brings attention to hip-hop culture and how it “represents and reflects on black subjectivity.” She points out that “black youth perform the effect of being seen and represented more generally.” By showing examples of girls hiring photographers for their prom, we can easily draw a parallel to the fashion and film industry (or “high-society” events in general) where being photographed on the red carpet is a must and causality at the same time however it is then seen by millions of “regular” people to admire and dream of being in their shoes one day.

Brian Mitchell, Prom Star, 2008

Paparazzi Photographing Celebrity at Red Carpet Event, Image by © Patrik Giardino/Corbis

Then there is hip-hop in art as in Kihende Wiley’s work where he uses figurative painting to talk about hip-hop culture. He uses bright color, vibrant pattern and typical though theatrical poses to illustrate it.

Thompson also mentions Luis Gispert, another successful artist from the same generation (and both graduates from Yale Univeristy’s School of Art) who photographed women cheerleaders. These images are also bright, the girls are embellished with gold, the poses are theatrical, even more exaggerated than in Wiley’s work.

Luis Gispert, Cheerleader, 2000-2002

One of the elements in Gispert’s series – the gold “bling” – is a common trait in hip-hop – “the term bling originally referred to expensive jewelry; quickly entered common parlance and by 2003 Oxford English Dictionary defined it not only as a “piece of ostentatious jewelry” but also any “flashy” accoutrement that “glorifies conspicuous consumption.”” Thomson makes a point that shininess in hip-hop has a larger background in art history – materiality and visual texture have been a part of painting, mostly Dutch, since the 16th century – a sign of wealth and economical prosperity. When talking about Hype William’s work, Krista Thompson states that “William’s hip-hop aesthetic calls attention to the failure of vision, to how vision obscures from view that it purports to reveal.” Thompson analyzes deeply the bling, its connection to the sound and racial signification. It is an interesting research. I have to admit that I don’t have a lot of knowledge in hip-hop and I don’t think because I’m white, it is simply not my “cup of tea”; it doesn’t mean either that I didn’t find it interesting to read this study and see how even classical painting has influenced contemporary manifestation in hip-hop culture.

To sum up the subject, I recognize how important it is in American culture, how long and painful the battle on racial equality has been and how important it is that there were no discrimination in this matter; and not only, in France, for instance, there are a lot of issues with Arabs – their traditional culture is not truly respected; French want everyone to be equal, the same, thus they have even forbidden the head veil in public spaces, such as schools, for example. There have been penalties, lawsuits, debates on the topic however French government says that Arabs can only be accepted in France if they accept their rules. As it comes to art, as I mentioned earlier, it seems it could be the safe space but it is also influenced by the events, by politics, by life; it is not isolated, it fuels the world and vice versa. Therefore, it is rather important to talk about the issues also in art.