“New Topographies”, a show curated by William Jenkins in 1975, showed the work of eight American photographers – Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore and Henry Wessel, as well as the German couple Bernd and Hilla Becher. In his introduction to the exhibition, William Jenkins discusses some important photographic questions, issues and notions.

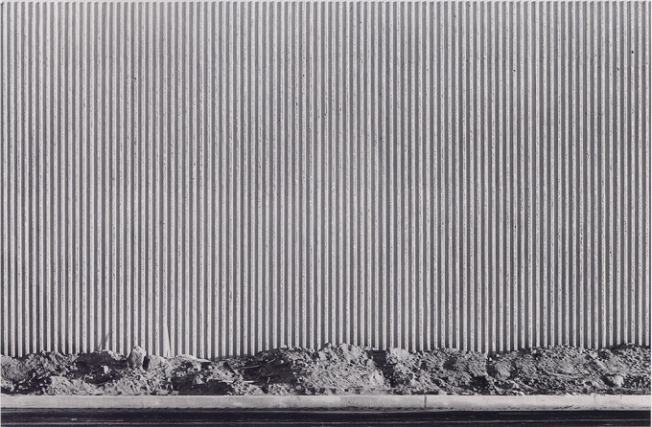

While talking about Edward Ruscha’s work which was an inspiration to a lot of the photographers in the show and to the idea of the curator, Jenkins resumes in a clear way what the topographics in photography mean: “The pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion, and opinion.” Also, he adds what an original meaning of the topography is: “The detailed and accurate description of a particular place, city, town, district, parish or tract of land.”

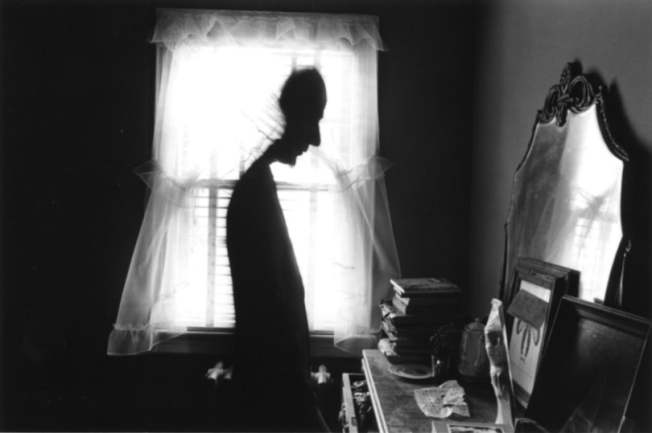

Nicholas Nixon states that he loves the contradiction of photography; “The best photographs are transparent, sensual, intelligent, fulfilled, freshly arrived, enduring and, in the deepest sense, are of the world.” This thought touches on Jenkins discussion about the “the photograph’s veracity”. Lewis Baltz reduces the photographic document as a “fully exercised observation and description” where there is no place for the artist. However, I think that Baltz’s style is apparent in his work, therefore, even if looking for the most clear document of the world, he cannot escape of showing it his way.

Jenkins sums up his introduction by saying that the exhibition’s goal was to question what it means to make a documentary photograph. Very interesting indeed, however a question that doesn’t have one answer.

Robert Adams, in the introduction for the exhibition, reveals that one of his favorite photographers is Timothy O’Sullivan, his photographs are the subject of Robin E. Kelsey’s essay. O’Sullivan photographed for the survey which main goal was to make topographic maps of the southwestern United States. The subjects of O’Sullivan’s photographs were landscape depicting mining sites or towns, landscape or river scenes, military forts and various subjects, among them, American Indians and geological formations. Here, I would put these photographs in the category “photographic document”; they really serve as a survey and even though the photographs are iconic and O’Sullivan can be recognized as the author, they don’t specifically reveal a stylistic element; yes, they are considered but a survey is a neutral document. However, as we learn later too, O’Sullivan’s work was a great influence to many American photographers.

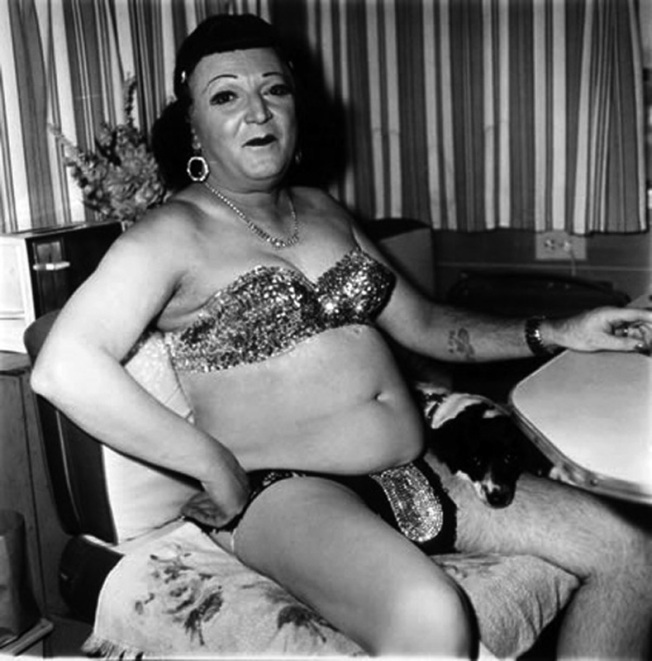

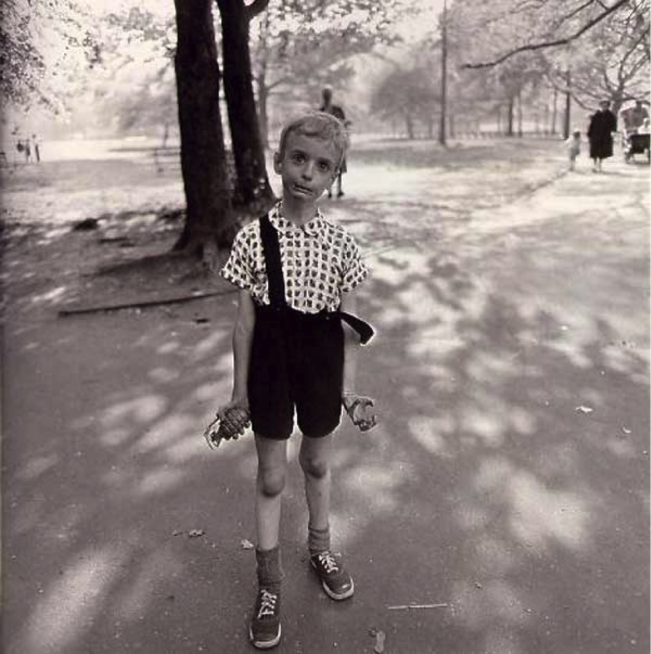

Toby Jurovics in his writing “Same as it ever was” looks back on the exhibition and claims it as one of the best and most influential exhibitions ever. Firstly, he compliments Jenkins on the choice of the photographers. He then tries to understand how the exhibition and Jenkins’ initiative was comprehended by the audience and what has remained until today. Jurovics believe that not only Jenkins simplified the idea of the topographies but it was for long also understood narrowly. Jurovics claims that “the challenges with interpreting New Topologies has been the inability to separate the subjects of these photographs from their meaning – what they are of from what they are about.” I would never describe Adams’s photographs as dull or flat, in fact, his Summer Nights Walking is one of my favorite photographic works and peace is one of the words I’d use when describing his work.

Frank Gohlke that Toby Jurovics mention in his text has suggested that “the tension between the form and meaning is not a dialogue solely confined within the boarders of the print but rests within the subjects of the photographs themselves, in our responses to their practical uses and cultural associations.” I think in the most of the cases we respond to a photograph with associations, based on our knowledge and experience however, as lot of them come from the common pool for all the humans, it is also possible to connect with the intentions of the author. To accent his assertion, Jurovics states the following: “The photographers in the New Topographics exhibition were not attempting to isolate and distance themselves from the landscape but to re-engage in a way that would be meaningful to contemporary experience.” Jurovics opposes to Jenkins’s statement about the fragile relationship between a subject and a picture of that subject; he adds that “Photography is the least fragile medium of all”. Interesting to discover that there are Adam’s images, “near duplicates of photographs of O’Sullivan’s” survey photographs. At the end, Jurovics adds that “these artists wanted to create a language of possibility.” I think that it is one of the potential roles of photography and its dialogue with the viewer.

From topographies as O’Sullivan’s survey photographs to the famous exhibition pictures, I was wondering what a similar exhibition would look like today, what photographers would be included. There are so many dealing with the questions of land, manmade space and the border between that at the nature. I would think of Michael Wolf, Edward Burtynsky, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Massimo Vitali, Simon Roberts among others.